223 Remington, 22-250, 220 Swift and Friends for Deer Hunting?

A few of the 22 centerfires legal for big game hunting in many places. But are they up to the job? (L. to R: 224 Valkyrie, 223 Remington, 22-250 Remington, 220 Swift, 223 WSSM.)

Want to start a fight? I mean a real screaming, name calling, foul language, glad-you-aren’t-within-fist-distance argument?

Recommend 22 centerfires for deer hunting.

Then double down by claiming they’re suitable for elk, too!

Turn down the volume and hang onto your hats, because here we go…

22-250 Pronghorn Shots

At roughly 110-pounds, the lightly-framed North American pronghorn may be the ideal big game animal to hunt with a 22-250, 220 Swift, 223 Remington or any other legal 22 centerfire.

I loaded a 55-grain Nosler flat base bullet atop a 22-250 Remington case. This was pre-chronograph days for me, but the handloading recipe suggested (promised?) 3,700 fps. From the 22-inch barrel of my Ruger M77 it was probably closer to 3,600 fps. Rifle, bullet, and I were going South Dakota pronghorn hunting.

I stalked within 300 yards of a buck. It decided that wasn’t close enough so walked 150 yards closer. I applied the 55-grain medicine behind its shoulder. It dashed 40 or 50 yards and fell over. Pretty much what pronghorns do when chest shot with 25-06, 270, 30-30, even 300 magnums.

This isn’t the pronghorn I took with my 22-250, but similar in size and response to the shot. Hit behind the shoulder, it ran a short distance, dizzied, and fell. A Cabela’s branded Winchester M70 in 270 Win. took this Wyoming buck. Optics were the excellent Cabela’s brand built for them by Meopta. The hat behind that Cabela’s band is the one I’m still wearing — and this photo is from 2011! The hat’s aging better than I.

Next up was a doe facing me at less than 200 yards. Crosshair on brisket. Down she went in a heap, reminding me of what a Fish & Game biologist once described as “lights out” every time he shot pronghorn with his 22-250. Smug and satisfied, I sat quietly while the rest of her band slowly fed away. About five minutes later, the collapsed doe jumped up to join them! A broadside shot to the chest stopped her. The first shot had deflected along the ribs and under the shoulder, hitting no vitals. Yet something — one has to believe the mysterious “hydrostatic” shock — had knocked her out.

A 22-250 Ackley Improved Holland Custom rifle pushing 60-grain Nosler Partitions 3,725 fps tipped this wide whitetail right over — twice!

My third 22-caliber success fell at the smack of a 60-grain Nosler Partition given added boost from a 22-250 Ackley Improved case. Muzzle velocity was 3,725 fps, measured. Target was a rutting 4x4 whitetail bedded beside a reluctant doe, only its head and neck showing. Neither grunting, whistling, nor shouting got him up, so I neck shot him. Over he went and off dashed his girlfriend. Before I could pat my Holland Custom rifle on the back, the buck stumbled to its feet and, a might confused, ran, angling toward me. At 150 yards he was racing as if he’d never felt such a thing as a the sting of 60-grain Partition. So I introduced him to another. He flipped heels over head, dead instantly. The little slug was later discovered to have broken the shoulder, punched through the spine, and exited the pelvis.

Not an aesthetically pleasing image, but it shows the entrance for the first 60-grain Partition that knocked this buck out for a few seconds. Then he rose and ran right into another partition.

Stories like these provide ammunition to 22 centerfire supporters and opponents. And they’re a dime a dozen. That both sides can’t agree is suggested by various state Fish & Game agencies, some of which allow use of 22 centerfires for big game hunting, some of which strictly forbid them. Oddly enough, those who permit it don’t seem to be running out of game nor even seeing more “lost-but-not-founds.” A few include Texas, Montana, South Dakota, Idaho, Georgia, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Alaska.

Historic Anecdotes Muddy the Waters About 220 Swift

Clearly the jury is still out. So what’s a hunter to do? Well, one approach is additional research that goes well beyond the “my brother’s wife’s cousin’s best friend’s friend shot a little doe with a 223 Remington and it ran off, never to be seen again! Twenty-twos are too weak for deer hunting! Use enough gun!”

22s too weak for deer? Maybe. But which 22? L. to R. 22-250 Rem., 22 Hornet, 223 Rem. 223 WSSM. All have been used to take deer. But that doesn’t mean they’re a good option. Or are they? The debate rages.

But there are also stories of does fairly struck by 300 magnums and never recovered, which explains the hunters you find roaming the Northwoods with 375 H&H Magnums during deer season.

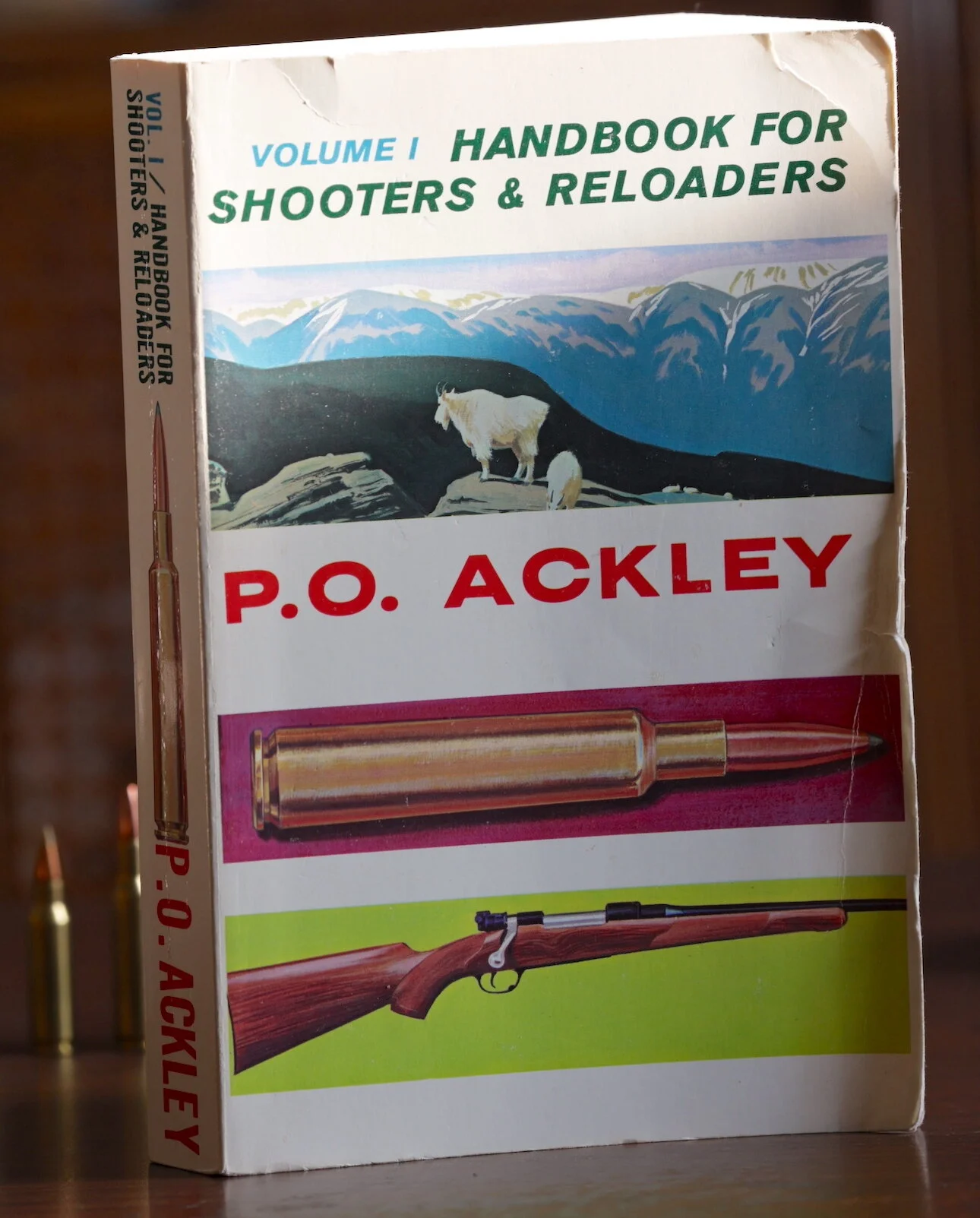

Muddying the waters further are moldy reports from professional cullers in Australia, Africa, and even Arizona where sharpshooters were once hired to eliminate destructive, invasive feral burros. One of these is famously recorded in P.O. Ackley’s Volume 1 Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders, copyright 1962. In a chapter titled “Killing Power,” Lester Womack, once a ranger in Grand Canyon National Park, relates the effect his 220 Swift had on feral burros north of the Park during a culling operation. His conclusion was that “the Swift made more clean, one shot kills than any other caliber used. Range seemed to make little difference… up to 600 yards.” Other cartridges used included 30/40 Krag, 30-06, and 8mm Mauser. Womack concluded by stating he would choose the 220 Swift above all others.

P.O. Ackley himself wrote in this same book, if I’m reading this right (it’s rather challenging to determine when Ackley is expressing his opinions or those of others like Womack) that “the 220 Swift is the greatest one-shot killer on deer and similar game ever produced.” But Cody, Wyoming guide and outfitter Les Bowman was quoted in this same book saying this about 22 centerfires: “I do not feel they are adequate, as the weight and quantity of material in such bullets does not allow enough for properly expanded size or weight for penetration.” (this was from the 1950s when, one supposes, most 22 centerfire bullets were the frangible varmint type with peak weights at 55-, perhaps 60-grains.)

Ruark Barks: Use Enough Gun (No mention of the bullet.)

The all time hero for the anti-22 team was the incomparable Robert Ruark, author of “Use Enough Gun.” Alas, Mr. Ruark had more experience with writing very well than shooting very well, so his assessment of the 220 Swift reached more ears than Womack’s. After wounding a warthog and then a hyena with his new, never-fired-before-the-safari Winchester M70, Ruark defamed the 220 Swift for eternity, never once mentioning the frangible 48-grain bullet might have been the culprit.

And so the debate continues with no resolution in sight. I’m certain this dissertation won’t change that, but let’s see if we can add a lumen or two of light to the btu’s of heat.

It’s the Bullets, Silly. (At least partly.)

Terminal performance with 22 centerfires hinges more on the bullet than the cartridge/rifle firing it. Ruark’s mantra should have been Use Enough Bullet!

First, the bullets. Today’s 22 centerfires fling bullets .224” wide. They are made in weights from 30-grains to 90-grains, shaped from flat-based and relatively blunt to extremely boat tailed and pointed like a needle. They are constructed to fragment on striking a four-ounce ground squirrel or punch through steel plate from which a 30-06 bullet ricochets.

Cartridges that throw these bullets run from 22 Hornet through 220 Swift and a whole bunch of wildcats and obsolete cartridges, some as “new” as the 223 WSSM, some as enticing as the 224 Texas Trophy Hunter. Velocities vary from about 2,900 fps (22 Hornet, 40-gr. bullet) to 4,300 fps (220 Swift, 40-gr.) The Swift can nudge a 75-grain 3,400 fps, perhaps a bit faster. My 22-250 AI sends it 3,350 fps.

22-caliber centerfires are not created equal. L. to R: 22 Hornet, 221 Fireball, 222 Rem., 223 Rem., 224 Valkyrie, 22 Nosler, 224 Wby. Mag., 22-250 Rem., 220 Swift, 22-250 Ackley Improved, 223 WSSM.

These high velocities are touted as one of the strengths of some 22 centerfires, velocity contributing more kinetic energy than mass. They say a grain of sand at enough velocity could vaporize the moon. Theoretically. Double a projectile’s mass and you double its energy. Double its velocity and you quadruple its energy. But how do you put that energy to work?

On small game, 22 centerfire energy literally explodes. Itself and the target. Frangible bullets disburse all the energy they’re carrying in one gasp, so to speak. On larger game these same bullets either sneak inside the rib cage and explode the heart and/or lungs, initiating rapid demise, or explode on muscle mass, initiating a long chase or additional shots.

22-caliber varmint bullets shot into soft wax cylinders, which were then sliced open, illustrate their explosive effect. Imagine a cavity of destruction like these in the thoracic cavity of a deer. But what if you accidentally strike major muscle mass instead of slipping those frangible bullets behind the shoulder?

This is the bullet failure performance Ruark and his PH Selby saw. Womack used tougher Barnes, Sisk, and Ackley bullets. While those are no longer marketed, there are suitable replacements such as the Nosler Partition, Nosler AccuBond, Swift Scirocco, Hornady GMX, Federal Fusion, Hammer Hunter, Cutting Edge, Badlands Precision and more.

But not everyone addresses their game with such controlled expansion, premium bullets. Many simply buy a cheap, cup-and-core bullet, apply it to the chest of their deer, and start skinning.

So what’s going on with these 22s? Can or should we really trust them for deer, elk, even moose? Yes, many north country residents routinely collect their winter moose meat with 223 Remingtons! How many they wound and lose, who knows?

The best we can do is investigate 22 centerfire ballistics to see what we’re up against. We’ll work with the ubiquitous 223 Remington and a 220 Swift. Readers can extrapolate up or down for other cartridges (the new but already obsolete 223 WSSM is a smidge faster than the 220 Swift.)

Ballistics Shed Some Light on 223 Remington & 220 Swift Performance

223 Remington, 53-grain varmint bullet

The 53-grain 223 Remington load represents what many casual hunters probably use for hunting whitetails from stands. Most know enough to shoot precisely and tight behind the shoulder. This results in the frangible bullet slipping into the rib cage before exploding into a cavity roughly three inches in diameter with bullet fragments perhaps reaching to the lungs on the opposite side. The result is rapid hemorrhaging, lung collapse, and a dead deer quite quickly. A strike to the heart or just above it is particularly deadly. The potential downside is that the bullet breaks up on the shoulder without reaching the vitals. Shot placement is critical.

Neck shots with these bullets can work dramatically as well, but it’s alway possible to strike too far from the spine to effect much more than a temporary shock and a bad muscle wound likely fatal but not soon enough to recover the animal.

223 Remington, 70-grain Nosler AccuBond

Stepping up to a heavier, more controlled expansion bullet like the Nolser AccuBond is represented by data in our second chart. Notice that initial energy from the heavier bullet is less than that of the lighter one, but at 100 yards the retained energy is already higher. Those who subscribe to the idea that 1,000 foot pounds must be applied to a deer to effect a quick, clean kill should note that this is reached at just 125 yards with the 53-grain bullet, about 150-yards with the much heavier 70 grain. Anyone who dotes on high energy for taking deer will realize the 223 Rem. limps off the field after about 150-yards. Might as well be using a 30-30. Except the recoil of the 223 Rem. is so minimal that kids and physically compromised adults can shoot it easily, painlessly, precisely. And I’ll again bet dollars to donuts a heart/lung shot at 200 yards, 250 yards, and even 300 yards — while not optimum — isn’t going to bounce off.

The Don’t Call It Swift For Nothing

The faster Swift extends 1,000 f-p performance significantly farther, carrying it a few steps beyond 375 yards! Let’s look at that trajectory table next because, to me, it is impressive.

220 Swift, 70-grain AccuBond

Anyone valuing energy on target can’t complain too much about this 70-grain bullet performance. The 150-grain from a 30-30 carries just 995 f-p energy at 175 yards, only 646 f-p at 300 yards. Those who insist penetration and, by association Sectional Density, are more important than energy shouldn’t find the 70-grain .224 bullet too shabby, either: SD .196. That’s not too far behind the 150-grain .308 at .226 and better than the 158-grain .358 at .177.

Velocity and energy are one aspect of potential terminal performance. Penetration and expansion, adding up to wound channel, are another. Can we really expect useful wounding form a puny 22 centerfire? Can momentum, and by extension penetration, possibly be adequate? Certainly. While mass is a huge part of momentum, so is velocity and bullet construction. A .224” bullet that expands to perhaps .448” (double frontal area) while retaining a good length of shank can and should penetrate well. This was dramatized by that 60-grain Partition I punched through that running whitetail. I once parked a 75-grain Scirocco in the brisket of another whitetail. It tore through the lungs and aorta and stopped against the diaphragm muscle. The doe ran the usual 40 yards or so and expired. Another taken behind the shoulder with a 75-grain Hornady A-Max — hardly an ideal hunting bullet — covered about 30 yards before giving up the ghost, no different than most deer do whether hit with 270, 280, 300 Win. Mag. and sometimes 50-caliber full patch conicals from my Hawken. The A-Max has since been retired, but a 75-grain ELD-Match sports even higher B.C.

22 Nosler and 224 Valkyrie Twist to Stretch the Range

Long and heavy for caliber bullets in the fast twist barrels chambered for 224 Valkyrie and 22 Nosler place them hard on the heels of proven deer killers like 243 Winchester.

The latest 22 centerfire iterations are the 22 Nosler and 224 Valkyrie, both designed for long bullets and fast twist barrels, both short enough to fit and function in AR-15-length magazines. The Nosler has a bit more powder capacity and calls for 1:8 twist. Federal’s Valkyrie is 1:7. Both stabilize extremely long, low-drag bullets as heavy as 85 grains. Neither is perfect with Sierra’s 90-grain MatchKing, so let’s run some numbers based on Nosler’s 85-grain RDF target bullet at 2,800 fps. That’s perhaps 100 fps slower than the 22 Nosler, 100 fps faster than the Valkyrie, but close enough to paint the picture we need to see.

22 Nosler, 85-grain RDF

The heavier bullet helps keep energy above 1,000 f-p to 300 yards. What the ballistic data doesn’t show is the increased penetration potential of a long, heavier, higher momentum bullet like this. Except construction is engineered for precision target accuracy, not terminal game performance. Unless and until someone builds tougher, controlled expansion high B.C. bullets for these two — or any custom barreled 22-250 or 220 Swift — they’ll remain tantalizing, but not ideal for hunters. On the other hand, careful shot placement tight behind the shoulder might suffice. It’s certainly worked for many 223 Rem. and 222 Rem. hunters tagging whitetails inside of 150 yards, according to reports.

At this writing, Hammer bullets offers several all-copper hollow points in .224. For faster twist barrels there are the 64-grain, 70-grain, 73-grain, and 83-grain Hammer Hunters. The latter needs 1:7 twist to stabilize.

Not all 22 centerfires have the horsepower to drive the long, heavy bullets that help make 22s effective on big game. L. to R: 22 Hornet, 222 Remington, 220 Swift.

Barnes’ 62-grain TTSX needs a 1:9 or faster twist. There are other fast twist, heavy .224 bullets out there. All we need now are manufacturers chambering fast twist barrels in 22-250 Rem. and 220 Swift. Because most do not, you might want to rebarrel with a custom fast twist. Shaw Barrels offers 22-250, 22-250 Ackley, 224 Wby. Mag., 22 Creedmoor, 224 TTH and 220 Swift in 8, 7, and 6.5 twist.

My conclusion on 22 centerfires for deer is kind of like campfire smoke. It shifts direction, but persists as a firm belief that the right 22 in the right hands with the right bullet at the right distance can be deadly effective on deer and similar sized game. It’s more problematic with elk and moose, but as plenty of careful shooters have demonstrated, it can work. But the same can be said of a 22 Long Rifle, and we’re not recommending that. Obviously larger calibers and heavier bullets leave more room for error, but none are the magic bullet that works every time. As many a hunter with broad experience has noted, better to hit the right place with a small bullet than the wrong place with a heavier one. Still, electing to hunt elk with a 22-250 Remington instead of a 300 Win. Mag. or 270 Win. or even a 6.5x55 seems risky if not downright foolish. It’s one thing if you have to, it’s another if you merely want to. Although if Mr. Womack were still around, he might disagree!

Do you really want to engage an animal as massive as this bull elk with a 22-caliber bullet of any kind? They can work, but range and placement must be perfect. There are dozens better options.

When it comes to hunting big game with 22 calibers, perfect shot placement commensurate with bullet construction and target distance are key. Minimal recoil helps most of us shoot 22s precisely. No flinching. If our mantra truly is shot placement uber alles, our 22 centerfires can be good enough “to ride the river.”