The New Magnum 30-06

Did you know the 30-06 of the 21st century nearly matches the 300 Winchester Magnum of the 1960s? With out the recoil?

Everyone knows the 117-year-old 30-06. Some love it, some revere it, some hate it, some laugh at it. Few fully understand it. I included. Before we put the old “ought six” out to pasture let’s put it in perspective via a close investigation.

The 30-06 Springfield of 1906 started as the US military’s official combat small arm, but quickly became one of the most popular and successful hunting cartridges in the world, taking everything up to and including elephant.

First, a bit of history. The 30-06 emerged first as the 30-03 in 1903. That round sprang from the plagiarizing minds of U.S. military men seeking to match the battlefield performance of the Spanish Mauser and the 7x57mm Mauser cartridge it fired. They undoubtedly looked at the German 8x57 too, since it was seminal in the development of the 7x57. So our guys basically took the 7x57mm case, lengthened it, and necked it to take a .308” diameter bullet. Initially that was a 220-grain round nose, but more forward thinking ballisticians quickly realized that a heavy, round-nose slug was not optimum for downrange performance. So they switched to a 150-grain spire point, shortened the -03 neck a smidgeon, and pronounced the 30-06 as the newest official U.S. military round. This was the USA’s first fully modern centerfire rifle cartridge that combined smokeless powder with high maximum chamber pressures (60,000 psi) and an aerodynamic bullet at substantial muzzle velocity. With the 30-06 Springfield we’d finally thrown off the shackles of the big, heavy, slow, blackpowder-era slugs.

The 7x57mm Mauser (left) was the foundation of the 30-06 (right) and, in turn, the 308 Winchester. All have the same rim and head diameters.

Eleven years later that 30-06 got to test its mettle. It went to Europe to prove itself against the German 8mm Mauser. It went back again in the early 1940s. The fact that we’re now speaking English suggests it succeeded. After WWII the good old “ought six” was retired to a backup role behind a shorter version, the 308 Winchester or 7.62x51 NATO in 1957. That round was soon upstaged by the 5.56x45 NATO, or 223 Remington, in the M16 battle rifle of 1964. And now that pipsqueak cartridge is about to be replaced by the 6.8x51 or .277 Fury cartridge.

Well now. If the military wiped its hands of the 30-06 clear back in the late 1950s, why should we common hunters cling to it in 2023?

Because it works. Better than ever.

This massive, 1,800-pound (estimated) eland bull fell to a single 180-grain Nosler AccuBond from a Federal factory load fired through a Savage M110 30-06. Elizabeth Spomer was the hunter, Werner von Seydlitz of Immenhof Safaris in Namibia the guide. I was the photographer and backup. No backup needed.

When the 30-06 first threw those early, military 150-gr. FMJs, they were rated 2,700 fps from a 24-inch barrel. The 180-grain slugs stepped out at about 2,500 fps. Hunters familiar with the 30-30 and 30-40 Krag saw the new potential and put the 30-06 to work, hiring firms like Griffin & Howe to sporterize the military Springfield rifle. Novelist and adventurer Stewart Edward White was one of the first to do this. He took A G&H 30-06 to Africa. Theodore Roosevelt soon followed White’s lead. In short order the 30-06 was satisfactorily applied to everything from coyotes and Coues deer to brown bears and elephant. It quickly established itself as the quintessential, all-American, general use big game cartridge King, cementing the 30-caliber as THE caliber of the United States.

Before you say “yeah, that was then but this is now!” and consign the old war horse to the dustbin of history, consider that today this same 30-06 case will push a 150-grain game bullet 2,900 fps to as fast as 3,000 fps. (Hornady’s Superformance loads are rated that fast. Handloaders regularly expect 3,000 to 3,050 fps from safe reloads.)

But increased velocity is not the only new feature of the old 30-06. A significant attribute is its ability, in 1-10 twist barrels, to handle bullets as light as 100-grains to as heavy as 220 grains, sometimes 230-grains. That is incredible versatility. Handload a 110-gr. down to as slow as 1,500 fps and you have a viable small game rifle and inexpensive training rifle. Load hot with 190-gr, super-high B.C. bullets like the Nosler AccuBond Long Range (B.C. .597) or 200 gr. ELD-X (B.C. .626) or Berger 210-gr. VLD Hunting (B.C. .631) and you reach ballistic performance unimagined in 1906. Flatter trajectories, less wind deflection, and more downrange energy than ever before.

Bullets from 100-grains to well over 200 grains have long helped the 30-06 be an extremely versatile cartridge, but today’s long, sleek, boattail bullets combined with new powders makes it faster and more powerful than ever.

Claiming better ballistic performance is one thing. Putting it into perspective is more revealing.

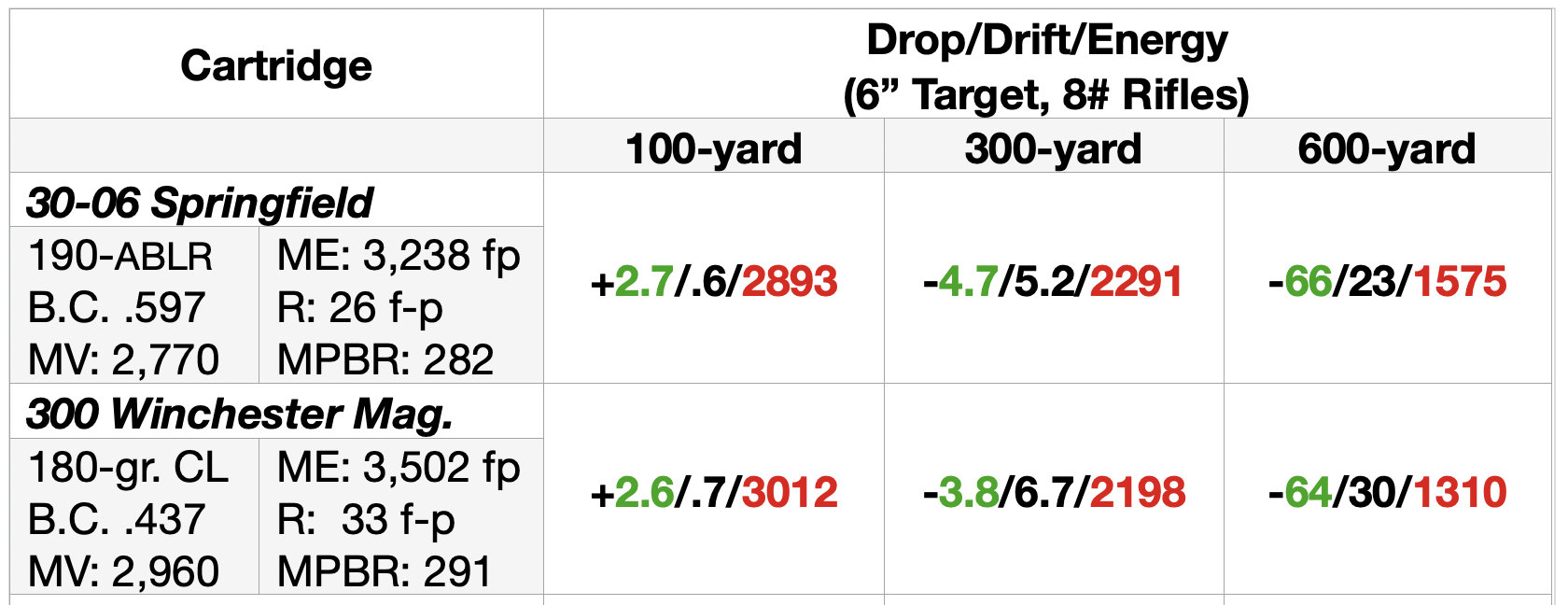

For those who think the 30-06 is an antique, let’s compare it against a 300 magnum long revered as a world beater, one of the best all-round cartridges for hunting virtually anything anywhere anytime — the 300 Winchester Magnum. No, this is not the fastest, most powerful 30-caliber in the world, but it is the one most hunters know, trust, and feel confident choosing. Recoil is heavy, but not so heavy that most can’t manage it at least well enough to hunt and shoot effectively. We can safely call it what it is — a “magnum” 30-06. So we’ll give the 300 Win. Mag. it’s due, but then let’s compare it to the new 30-06. Study the ballistic chart below to see how close the doddering 30-06 comes to the performance of a traditional 300 Win. Mag. load. An inch more drop, 1.5-inches more wind deflection at 300 yards, and 100 foot-pounds less energy at 300 yards. Neither you nor your quarry are likely to notice any of that. Out to 300 yards the new 30-06 is essentially the original 300 Win. Mag.

Notice the 30-06 still leaves the muzzle about 200 fps behind the 300 Win. Mag., but more revealing are the Maximum Point Blank Ranges. The vaunted Win. Mag. beats the 30-06 by only 9 yards. With today’s laser rangefinders, who cares? Then look at 300-yard wind deflection. The 30-06 is just 1.5 inches worse. Finally, check the 300-yard energies. If 2,291 foot-pounds aren’t enough for dropping your deer, elk, moose, bear, kudu, eland… Well, the 300 Win. Mag. isn’t going to make much difference. Finally, check out those 600-yard energy numbers. The 30-06 actually puts 265 foot-pounds MORE energy on target.

You’ll notice that I enhanced the 30-06 by using a modern, high B.C. bullet while hamstringing the 300 Win. Mag. with an old low B.C. hunting bullet, but this is intentional so as to highlight our new perspective. We know and revere the performance of a 300 Win. Mag., but that familiar performance was pretty much ironed in with common loads like the 180-gr. Remington Core-Lokt used in these trajectory calculations. This is a cup/core bullet quite similar in form and construction to the Federal Speer Hot-Core, Winchester SilverTip or Ballistic Silvertip, Federal Soft Point and others with which the 300 Win. Mag. made its reputation. If we’ve long thought the 300 Win. Mag. was Mr. Wonderful, a world-beater cartridge, we now have to agree that the doddering 30-06 hammers hot on the heels of that performance while burning a lot less powder and generating a lot less recoil.

Naturally, one can improve the 300's terminal performance with a number of controlled expansion bullets such as Swift A-Frame, Nosler Partition, Hornady Interlock with similar B.C. ratings, but by comparing the traditional bullets/loads, we put the “modern” 30-06 in a new light. It’s not that far behind the magnum we used to imagine was vastly superior to the ought six.

My second bull moose fell to one 200-grain Nosler Partition sent from my Winchester Featherweight M70 chambered 30-06. My first had fallen to a silly little 150-grain Federal soft point.

Of course there are now even larger, faster 300 magnums that’ll leave even the fastest 30-06 in their wake, but at what price? More powder, heavier bullets, more recoil, more expensive ammo. And for what? Sure, if you’re trying to win a 1,500-yard target competition, no holds barred, roll with the biggest 300 magnum. If you feel you must have a 250-grain hunting bullet to lay low a moose, pick up a 30 Nosler or 30-378 Wby. And enjoy the weight, length, and recoil. But for the average hunter, the man or woman who will be stalking more whitetails, mule deer, and pronghorns than moose, brown bears, and rhinos, a 30-06 makes more sense. Lighter rifle, less recoil, more than sufficient energy and reach for 95 percent of your needs. And I’ve witnessed first hand time and time again how effectively the 30-06 terminates big bull moose.

This, then, is the new way to assess the 30-06. Sure, we should remember what it’s been and what it’s done, but before we assume it’s glory days are gone forever, consider how it performs with new powders, new bullets, and new rifles. And then put this in the perspective of what we truly need in a field rifle. Do we really need a rifle to drop rocks on bucks at 817 yards? Or will most of our game be addressed inside of 500, 400, or 300 yards? An honest assessment should tell us that an emphasis on extreme-range performance is more applicable to target games and steel plates than hunting. Unless we’re exponentially poorer hunters than were our grandfathers.

The same 180-grain XP3 bullet shot into wax test tubes show that the 30-06 on left penetrates about two inches less than the 300 WSM (which duplicates the MV of the 300 Win. Mag.) The 30-06 carves a slightly narrower wound channel, too, but I doubt even the biggest, toughest animal would survive it.

As the ballistic chart below shows, the latest and greatest 300 PRC cartridge flinging one of the best, high B.C. hunting bullets Hornady loads in its Outfitter line of ammo beats the best 30-06 load by just a couple of inches at 300 yards. The 30-06 bullet still carries more than 1,500 foot-pounds of elk flattening energy at 600 yards.

Is the 250 foot-pounds additional energy in the PRC bullet really needed? Do we want to endure another 10 f-p of recoil to get it? Luckily, each of us gets to decide.

Another consideration, of course, is lighter bullets. We don’t all hunt elk, moose, eland, and bears. I’d wager more whitetails and mule deer are taken with 30-06 rifles each year than bigger stuff, and for those 150-grain bullets are often a grand choice. Flatter trajectory, lighter recoil. So how does today’s 30-06 hold up when shooting a fully modern, all copper Hammer Hunter bullet weighing 151 grains? Let’s compare it to the wildly popular 6.5 Creedmoor deer cartridge in the following chart:

How about those apples? At 300 yards the 30-06 shoots flatter and carries a smidgeon more energy. The 6.5 Creedmoor deflects two-and-a-half inches less in a crosswind thanks to its much higher B.C. bullet. Surprising might be the 30-06’s MPRB — 11 yards better than the Creedmoor. At 600 yards the Creedmoor is clearly superior in deflection and energy, but drops only 2 inches less than the stodgy old 30-06. Given how many of us engage deer at 600 yards, I suspect we’re safe employing the 30-06 to do our heavy lifting.

Either cartridge is a fine choice. Let’s just give the 30-06 its due. The old war horse has been used to deadly effect on everything including polar bears and elephants. It is fully capable of leveling the biggest Cape buffalo. If the likes of Stewart Edward White, Col. Townsend Whelen, Hemingway, Elmer Keith, Roosevelt and thousands of other hunters did this back in the days of lesser bullets and lower velocities, imagine what we could do with it now.

Put the 30-06 out to pasture? I say leave that pasture undisturbed. It’ll be decades if not centuries before the 30-06 is ready for it.