Which Standard Length .375 Caliber Cartridge Is Right for You?

Since its introduction in 1912, the venerable .375 Holland & Holland has been the benchmark for all medium-bore cartridges. Its caliber is the minimum for dangerous game hunting in many African jurisdictions, and with adequate bullets, it’s a sensible choice even for elephant hunting. With lighter bullets, it is astonishingly flat-shooting and great on small to large thin-skinned animals worldwide. The .375 H&H is therefore considered to be one of the most versatile all-around hunting cartridges.

The cartridge was developed in the age of cordite fuel, and the long and sleek case with a narrow shoulder helped with reliable function with the use of cordite. It also made for smooth feeding characteristics. On the other hand, it led to concerns about headspace. That is why engineers came up with a belted case to ensure proper positioning in the chamber. This feature has been carried over to many cartridges, although rarely necessary.

The grand old lady of the .375‘s launches 270-grain bullets with a muzzle velocity of 2,690 fps for a stiff 4,337 ft-lbs of kinetic energy from 24-inch-long barrels. Loads like that have a trajectory very similar to .30-06 loads with 180 grains bullets, depending on bullet shape. Lighter bullets weighing down to 235 grains drop even less when only the first 300 yards are considered. For practical hunting, use this cartridge with all the reach you need. The 300-grain dangerous game loads still have a muzzle velocity of 2,530 fps and carry 4,263 ft-lbs of energy. Heavier bullet choices of up to 350 grains exist, giving the hunter a broad spectrum of bullet weights, even in factory loads.

Now that I outlined the benchmark let’s look at a slew of .375 inch diameter cartridges developed to do the same, but from a shorter action. Developments of modern powders and new knowledge of ballistics opened the door for engineers to achieve just that. The .375 Ruger, the .376 Steyr, and the 9.5x66mm Super Express vom Hofe all compare quite well to the classic safari cartridge. Interestingly, if it weren’t for the British Empire to exclude all cartridges with a bullet diameter of fewer than .375 inches for dangerous games, all three would have been superfluous. The 9.3x64mm Brenneke from 1927 can do all that the .375 H&H does but fits neatly in a regular Mauser 98 action. The .366-inch bullets lack 0.009 inches in thickness to be legal on dangerous games in some African countries, but energy-wise, some loads will even outperform the sleek British cartridge.

Left to right: .375 h&H, .375 Ruger, 9.5x66mm SE, .376 Steyr

Young and Popular: The .375 Ruger

The first cartridge I want to take a closer look at is the newest of the group. The .375 Ruger was developed without a parent case in a joined effort of Ruger and Hornady and released in 2007. The beltless case is as wide at the base as the .375 H&H is at the belt. That and less case tapering mean more room for powder (99 grains of water) compared to the H&H (95 grains), even though the Rugers case is considerably shorter. Since maximum chamber pressure is almost identical, this translates to potentially higher velocities of bullets of a certain weight. Which is the case, with the .375 Ruger surpassing the older cartridge by roughly 100- 150 fps, depending on the loads you look at.

Since its introduction, the cartridge has gained a dedicated following. Some notable hunters and outdoor writers praise its effectiveness in African games and North America. That’s no surprise.

Compared to the other contenders in this field, a huge plus of this cartridge is its availability. Several Ruger‘s rifles are chambered for the cartridge, with 20-23 inches long barrels. Other companies like Mossberg offer more models to choose from. Hornady produces ammunition with bullets ranging from 250 to 300 grains. The selection of .375 bullets is huge, so the handloader has even more ways to find a good fit for their hunting. This is also true for the other pills, of course.

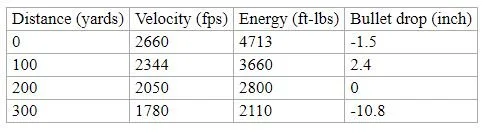

To assess the cartridge’s performance, I think it’s helpful to look at a few ballistic numbers. The following table shows velocity, energy, and bullet drop out to 300 yards for the 300 grains Superformance DGS (a full metal jacket bullet for deep penetration on thick-skinned games) factory load shot from a 24-inch test barrel. Few people will use a .375 caliber cartridge for long-distance shooting or hunting. You just don’t shoot at a buffalo, hippo, elephant, or bear that far. At least not as long as you like your body unscathed at the end of the hunt.

Ballistics of the 300 grain .375 Ruger

This is some serious production. Of course, the lighter 250 and 270-grain bullets shoot flatter but are not as good on the toughest critters. But other big, heavy animals like eland, moose, or bison will not like those projectiles. In the end, this cartridge leaves little to desire. If you’re a guide in need of a stopping rifle for dangerous game, a bigger bore is probably better. But for a client whose job is to put a precise first shot on target, this cartridge balances power and recoil very well.

Older, Unknown, but Also Powerful: The 9.5x66mm Super Express Vom Hofe

Most people have not heard about this cartridge, but that is a pity. If this cartridge was released in 2005, Ruger and Hornady would have been in serious trouble trying to sell their .375 afterward.

Left to right: 9.5x66mm SE and the .375 Ruger

German gunsmith Walter Gehmann developed the 9.5x66 SE after the English company, Westley Richards, wanted to build a standard length .375 cartridge. The cartridge was named the .375 Westley Richards for the English market.

Gehmann had experimented with different versions of a shorter .375 that would meet or exceed the .375 H&H‘s performance. Rather than simply necking up the 9.3x64 Brenneke, he finally decided to use his 7x66mm SE vom Hofe as a parent case. By widening the neck to hold 9.5mm/.375-inch bullets and giving the case a sharper 40-degree shoulder, he created a very modern-looking cartridge -- short, steep shoulder with a rebated rim.

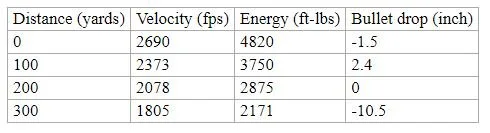

The cases have a lot of room for powder, which is why the cartridge was able to shoot 300-grain bullets as fast as 2690 fps in factory loads. No manufacturer loads for the cartridge today, but assuming one stuffs the cartridge with the same 300-grain bullets used in the .375 Ruger to these velocities, the ballistics are very similar, even a tad better.

Take a look at the following numbers and see how good the cartridge was. Basically, and ballistically, it is the .375 Ruger.

Ballistics of the 300 grain 9.5x66mm SE

Now compare the two cases. They even almost look identical, not only at first glance but also at second glance.

Unfortunately, the cartridge never caught on in the shooting world. The dominance of Holland and Holland was just too much for a cartridge that was developed way too late for the golden age of African Safaris. And since North American hunters disliked metric calibers for a long time, there simply was too little use for a cartridge like this. European game animals fall to smaller bullets, so why use that many guns? And that little hunting that asked for a hitter of this class could be done with a 9.3x62mm or a 9.3x64mm, which had long been established in Central Europe.

But if any of the major ammunition manufacturers decided to revive the cartridge with aggressive marketing and pair that with an affordable modern rifle option, little could hold a cartridge with these specifications back. A Mauser-type action, wooden stock, blued barrel, and iron sights. That would be a terrific combination for any African dangerous game hunt. Or maybe a synthetic stock for maximum durability in wet Alaskan conditions. I can see that one work, too.

Smaller and More Specialized: The .376 Steyr

Left to right: The shortest of the group, .376 Steyr, compared to the magnum length H&H

For this one, Hornady teamed up with the Austrian rifle manufacturers of Steyr. They intended to build a .375 caliber cartridge for short, handy scout rifles. The cartridge was designed to give a .375 H&H-like performance from these short-barreled bolt action rifles envisioned by Jeff Cooper. Despite its name, the .376 Steyr launches the same .375-inch caliber bullets. That allows its use on dangerous game all over Africa, which was one of the criteria for the so-called “lion scout.”

Realizing the velocities and kinetic energy of this class of cartridges from barrels as short as 18-19 inches is quite a task, but today’s knowledge about ballistics and powders makes it possible to realize the idea. The cartridge was based on the standard length 9.3x64mm Brenneke. Necked up to hold .375 bullets and shortened by 4mm, the cartridge neatly fits Steyrs’ standard length action.

In 2000, the companies revealed both the .376 Steyr and the Steyr scout rifle to the shooting world. That particular gun had a 19-inch barrel. Later, Steyr offered its Pro Hunter rifle chambered for the cartridge with a still convenient 20-inch barrel. Today, both are out of production, so used or custom guns are your choice.

For controlled expansion, Hornady produces two loads with InterLock sp-rp (spire point recoil proof) bullets. One full-power load with a 270-grain InterLock and a 225-grain bullet with reduced power. These are good for big game hunting in general, but I doubt anyone would use one of these for the really dangerous and heavy critters. Unfortunately, there is no full metal jacket or solid bullet for deepest penetration on thick-skinned animals, which hurts the cartridge’s usefulness in Africa. The broad selection of .375 bullets to choose from compensates for that, but only for hand loaders.

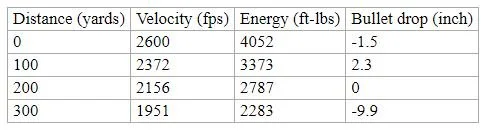

To see what you can expect from the .376 Steyr, let’s look at the ballistics of the .270 grain factory ammunition. You’ll notice that both velocity and energy are not that far behind the .375 H&H. But even with a lighter bullet, the velocities of the .375 Ruger and the 9.5x66mm SE vom Hofe are still higher with their 300-grain slugs. The test barrel that Hornady used to measure their advertised data was 26 inches long.

Ballistics of the 270 grain .376 Steyr

The ballistic curve is quite similar to the other cartridges, but the only category the .376 hangs with the other two. And only with a lighter bullet, at that. Velocities and energy simply can’t reach German or American design. One must consider that the .376 was developed for shorter barrels, so I would expect a lower production when fired from a scout rifle. But contrary to the assumption that you lose around 25-30 fps with every inch less, renowned German handloader and rifle nut Norbert Klups tested the cartridge from both 19 and 24-inch barrels and could only measure a speed loss of 45-50 fps overall. I can neither confirm nor refute this, but I can imagine that certain powders can be burned in short barrels where longer tubes don’t give a considerable advantage anymore.

There is one aspect where the .376 Steyr has a true advantage. The short barrels are best suited for moderators. This might be the best option if you’re interested in hunting with less muzzle blast. Longer barrels are not ideal for moderators, as overall rifle length hinders hunting in denser vegetation.

In the end, the cases of the .376 Steyr simply don’t have the same capacity as the other cartridges. There is just no way around that. Consequently, the performance level is behind the benchmark, and the other two standard lengths are .375. But that doesn’t mean the design is bad or a failure. The opposite is the case, in my opinion. It still hits with quite some authority. A rifle as handy as a scout gun, launching a still, powerful projectile, should have found its place in hunting. Also, consider that the bullet construction and shot placement are more critical to humanely killing an animal than bare energy or speed.

Following wounded bears into thick brush, elk hunting in dense woods, tracking big antelopes or dwarf buffalo in African jungles. Or big wild boar and heavy stags in Europe, too. The Steyr would fit all these purposes. For the thick-skinned game, I’d choose one of the others. But for anything else, this cartridge is a sound choice.

But apparently, performance is not the only factor deciding if a new cartridge can establish. Marketing and trends factor in, among others. The argument that some cartridges are superfluous is moot. Since the fifties or the sixties, most new cartridges have been somewhat superfluous and only show moderate improvements compared to older options.

In the case of the .376 Steyr, I think it might be too specialized for the broad majority of hunters. How many scout rifles do you see at the range or while hunting? That doesn’t mean it won’t work in other rifles, just like the pro hunter from Steyr, but there are other cartridges for that type of hunting. The .338 Winchester Magnum, the .35 Whelen, the 9.3x62mm, and a few more work fine for the same sort of hunting. And the two mentioned .375 cartridges offer more potential on the upper end of the scale. So there’s not too much demand for the .376 Steyr.

Which One Is Right for You?

The right choice for you is a question of personal preference and the type of hunting you’re doing. If you enjoy the flair of old Africa and the guns associated with that era, go with the .375 H&H. The long action is not that big of a disadvantage that this cartridge will be pushed aside by either of the shorter pills. It works, it’s classy, and it will be around in another hundred years.

The .375 Ruger will probably be the standard length choice of the future. There is a lot of power for its length and the widest distribution of all the shorter .375s. If you repeatedly hunt dangerous game, these might be the best-described pills.

For hunters who enjoy trying unfamiliar cartridges, the 9.5x66mm Super Express is a great choice, too. Performance-wise, it offers all you can wish for. Just make sure you find a way to supply yourself with ammunition.

The .376 Steyr is another oddball. It will serve best in a short brush gun and will even be fine for the hunter going on an occasional dangerous game hunt when an elephant is not of interest.