The Versatile 223 Remington

Perhaps the oddest thing about the 223 Remington is how and why it was adopted by the military. They went from 45-caliber to 30- to .22? From 405-grain bullets to 220-grain to 150-grain and then clear down to 62 grain? From 3,000 foot-pounds of energy to 1,300 f-p?

Yes, they did. And in the process we got our most useful, versatile, light recoiling, inexpensive, accurate 22-caliber centerfire cartridge. But sport hunters got it before any military did! Yup. the 223 Remington was introduced as a sporting round before military round. Here’s how it happened…

A few shooters think the 223 should not be used for hunting because it was engineered “as a military cartridge, not a hunting cartridge!” But that’s only half true. The military’s search for a new cartridge that would function to its standards in the new Stoner ArmaLite 15 rifle started with the little 222 Remington, a civilian, sporting 22-caliber that set all kinds of accuracy records after its introduction in 1950. That predates the 308 Winchester, the 243 Winchester, and Elvis as pop star. In 1950 Eisenhower wasn’t even president yet.

As most of us know, the 223 Remington in military circles is known as the 5.56x45 NATO. It’s longer and more powerful than the 222 Remington only because the military looked closely at the 222 and it didn’t quite measure up. It failed because it didn’t retain supersonic velocity (about 1,080 fps at sea level) and penetrate a steel helmet at 500 yards. The Army ordnance department then invited cartridge designers to give it their best shot. I love this part. Rather than design in house using government employees, they allowed, nay invited, ordinary U.S. citizens to create the cartridges! Yankee ingenuity to the rescue.

The Remington 222 first caught the military’s eye and initiated the search/creation for what became the slightly longer 223/5.56.

Meanwhile, Gene Stoner’s ArmaLite AR10 rifle in 308 Winchester was impressing The Brass, but it proved too difficult to control in full auto, so Stoner teamed up with Bob Hutton at Guns & Ammo magazine to create a lighter recoiling cartridge for a downsized AR rifle. The combo ultimately became the 5.56 NATO and M16, but first…

At this same time, Remington engineers were working with Springfield Arsenal to concoct that new cartridge. They came up with a lengthened version of the 222 that exceeded the 500-yard velocity standard, yet The Brass rejected it, too, possibly because it was a smidge too long or reached chamber pressures judged excessive for the AR action.

Rather than waste its R&D efforts, Remington took the new round to the streets. They released it in 1958 as the big brother to the beloved 222 Remington. They called it the 222 Remington Magnum. Perfect name for the times. It held 20% more powder to churn up 100 fps more muzzle velocity. That gave it another 50 yards or so of point blank range, a useful advantage for varmint and coyote hunters. And, since the 220 Swift was suffering bad press for eating barrel throats and the 22-250 was still just a wildcat, it seemed as if the 222 Rem. Mag. was on its way to stardom except…

By 1960 the 222 Rem. Mag. (far R.) looked poised to become the new favorite 22 centerfire, eclipsing the 222 Remington (far L.) But then the intermediate 223 Remington hit the streets. (Photo by the incomparable firearms expert Mike Venturino)

The Stoner/Hutton coalition in 1957 concocted a version of the 222 that hit the military jackpot. A bit shorter than the 222 Remington Magnum, their new 22 cartridge hit performance parameters and functioned well in Stoner’s new, scaled down AR15 rifle. But you know how fast the government works. By the time the generals got around to thoroughly testing and accepting this new “extended 222,” the Beatles were rocking the charts and Remington had released the “experimental” cartridge as the 223 Remington.

This was one of the better marketing moves Remington ever made. Just as Winchester had capitalized on the 7.62x51 military cartridge by taking it public as the 308 Winchester in 1952, Remington bet on the right horse with the 223 Remington. The US. military didn’t officially adopt it until 1964 as the 5.56mm ball, M193 cartridge shooting a 55-grain bullet. NATO didn’t grab it until 1980 and then only after they’d increased bullet weight to 62 grains and rifling twist to 1:7 inches. Other, heavier, specialty bullets have been used, too.

After Remington released the 223 Rem, it was long before other ammo makers jumped aboard. Today virtually everyone who makes centerfire metallic cartridges loads the 223 Rem.

All of these military machinations throw a pall of smoke over the 223 Remington/5.56 NATO relationship. Can you shoot them interchangeably? Technically the cartridges have the same dimensions. Rifle chambers do not. Military chambers usually sport longer throats (leades) with a more gradual ramping to the bore diameter. Firing commercial 223 Remington ammo in a 5.56 chamber shouldn’t be a problem, but firing, say, a 62-gr. or 77-grain military 5.56 round in a commercial 223 Rem. chamber could be. Not only do you risk raising pressures due to a longer bullet potentially kissing the rifling, but your barrel twist might not be quick enough to stabilize the longer projectile anyway.

There is also confusion about maximum average chamber pressure levels. SAAMI certified the 223 at 55,000 psi, but some military specs put the 5.56 at 58,000 and Europe’s CIP gives both 62,366 psi. What’s going on?

Apparently the different pressure numbers are all about the testing techniques. Depending on where and how they measure pressures these numbers give different readings, yet are essentially the same.

Despite this confusion, the 5.56 military round has assuredly helped the 223 Remington hunting round achieve its high status as one of the top selling centerfire rifle cartridges in the country. The majority of this ammo might be applied to targets, but that hardly means the cartridge is illegitimate for hunting a wide diversity of game animals.

Fun targets probably account for most 223 Remington fired.

As a varmint/predator cartridge, the 223 Rem. splits the difference between the “hard-on-barrels” 22-250 Rem., 220 Swift and now the 22 Creedmoor (and possibly 22 Nosler) and the “not-quite-fast-enough” 222 Rem., 218 Bee and 22 Hornet. A good 223 load will burn about 26-grains of Benchmark powder to reach 3,400, perhaps even 3,500 fps from a 24-inch barrel. If you really want to scream, try 28-grains Benchmark behind a 40-grain bullet and maybe reach 3,867 fps (according to the Nosler Reloading Guide 9.) Of course you need to include the proper primer and seating depth and cautiously work your way up to a full-house load like this to be safe, but it suggests the 223’s potential.

Despite the rash of 22 centerfires on today’s market, the 223 Remington (4th from L.) remains the most popular. L. to R. are: 22 Hornet, 221 Fireball, 222 Rem., 223 Rem. 22 Valkyrie, 22 Nosler, 224 Wby. Mag., 22-250 Rem., 220 Swift, 22-250 AI, 223 WSSM.

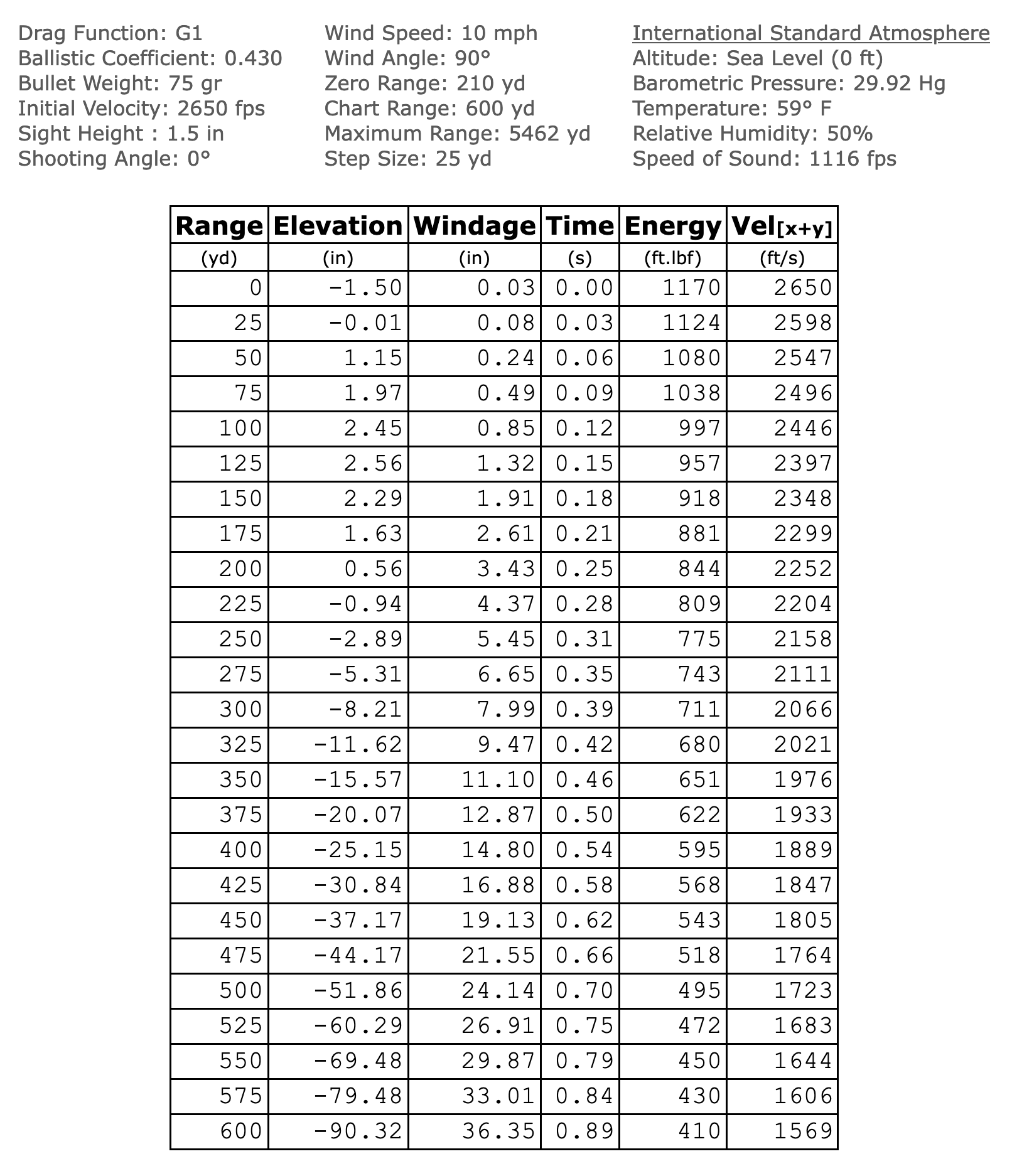

At the upper end, if you have the twist for it, is a 75- to 77-grain bullet at 2,697 fps. The Nosler guide reports this from a 20-inch barrel. I’d figure about 100 fps more from a 24-inch tube. My 1st Edition Berger Bullets loading manual lists 77-grain loads as fast as 2,832 fps from a 24” barrel.

Obviously the 223 Rem. is effective in battle, personal defense, shooting competitions like 3-Gun, rodent control, and predator hunting. That’s a long enough list to justify adding this chambering to any battery, but it’s incomplete. For a hunter the 223 can be a perfect training rifle. Recoil in a 7-pound gun is just 4.84 f-p, almost 3-times less that the kick of the easy-shooting 243 Winchester pushing a 100-grain bullet. Start a new shooter with that and forget about flinching. You can concentrate on breathing, positioning, and total gun and trigger control.

Whether chambered in an AR-15 or bolt-action, the 223 Remington may be the ideal varmint and fur cartridge in our arsenal.

The other benefit for field training is the familiar trajectory curve of the 223 Rem. Out to 300 yards or so it is kissing close to the drops and drifts of many popular deer hunting rounds. This means you can zero for maximum point blank range or use any drop compensation reticle or turret dialing scope to perfect field shooting. Given the relatively low cost of 223 Rem. ammo, this saves money as well as your shoulder.

Anyone who really wants to save money and reduce recoil can try handloading reduced loads. With the right combination of primer, powder and bullet, you can get 223 Remington muzzle velocities as low as 1,200 fps, right in the 22 LR rimfire ball park. Go squirrel hunting with your coyote rifle!

Texas probably sees more whitetails taken with 223 Remingtons than any other state. This buck, however, fell to a Browning A-Bolt in 270 WSM.

Hang in there. We’re not done yet. Despite its size, the 223 Remington can be an effective pronghorn, whitetail, Coues deer, mule deer, javelina, even feral hog cartridge. I’m not saying it’s ideal, but thousands of hunters employ it on these species every year. Most keep coming back, claiming it kills surely. You have to use the right bullets and put them in the right spot, but too many of these animals have been felled by a 223 Rem. to pretend it can’t fulfill the mission.

As long as we’re pushing the envelop, let’s blow it right open by admitting that many hunters also take caribou, elk, and moose with the 223 Rem. I know, sounds crazy, maybe even stupid, but it’s done. And often. How? Once again by putting the right bullet in the right place. A fairly frangible .224 bullet hauling just 1,000 f-p energy at 175 yards can punch through moose hair and hide, probably a rib, and “explode” in or over the heart to create massive hemorrhaging. A controlled expansion bullet will penetrate better, carve a smaller wound channel, but still disrupt enough blood vessels and deflate the lungs sufficiently to cause a big deer’s demise. Will it rock even a small caribou to its knees, punch through, or leave a massive blood trail? Probably not. But heart/lung shot animals are running on borrowed time. Tracking may be required. Heavy brush isn’t the best habitat in which to use a 223.

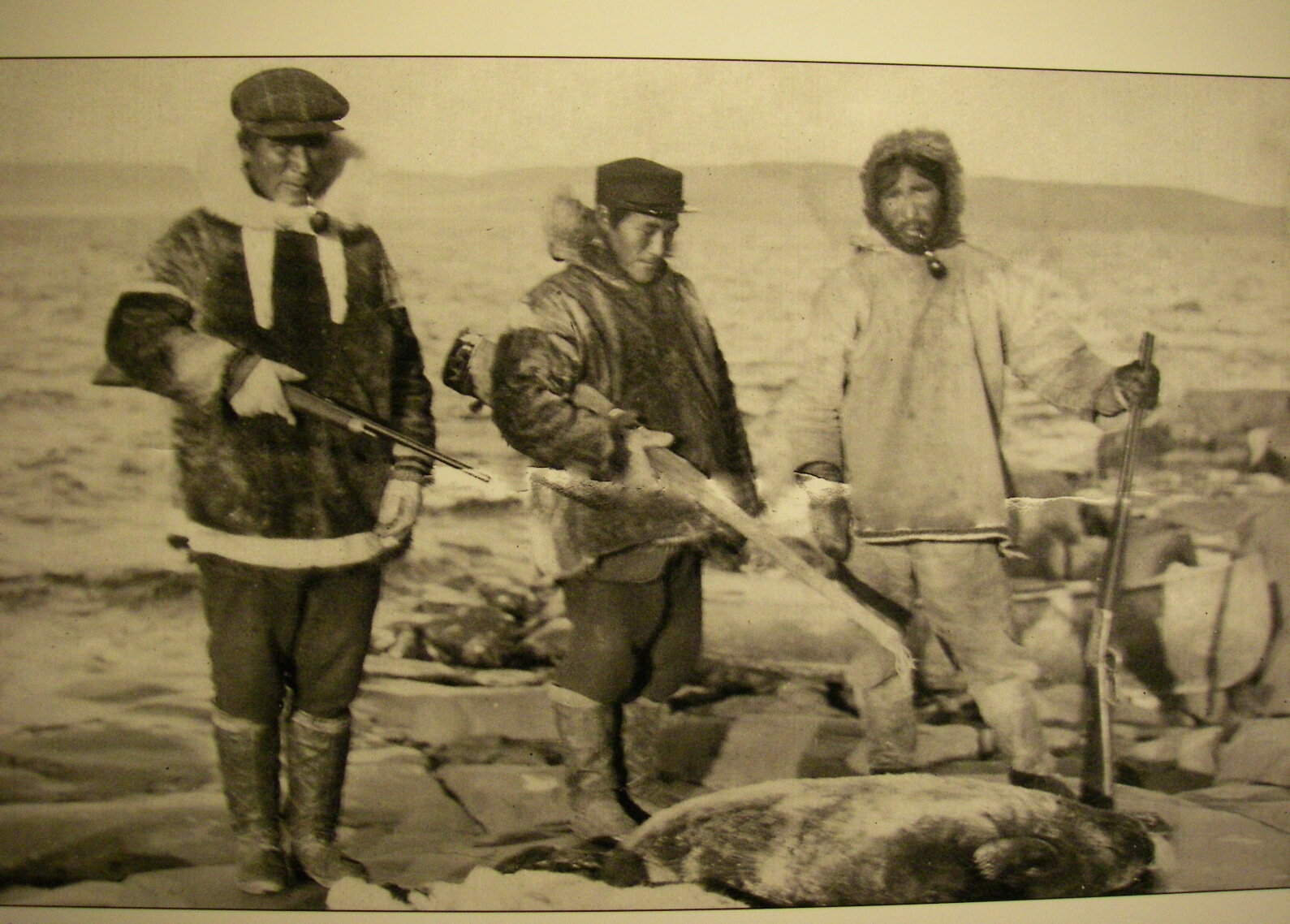

Subsistence hunters in the north use the 223 Remington surprisingly often. I, on the other hand, hired a 325 WSM to take this bull.

Do I recommend a 223 for elk or even deer? No, but if doing so means you are better able to park the right bullet in precisely the right place and your state F&G agency allows it, who am I to say you can’t do it? Most deeply experienced hunters know that a small bullet in the right place beats a large bullet in the wrong place.

Despite the “3” in its name, the 223 Remington handles common .224” bullets from 35-grains to 80-grains — if your barrel has the twist rate to stabilize them.

Other selling points for the 223 are widely varied and available ammunition and low prices (in normal times, anyway) and even wider bullet options for handloaders. Brass is readily available as 223 Rem. or 5.56 military. Both can be used in 223 chambers. Just be sure to resize, measure, trim, perhaps neck turn, etc. your brass to standard dimensions. Use bullets appropriate to your rifling twist and seat them at the proper depth.

Wonderful though the 223 Remington is, there is a downside: it killed the 222 Remington Magnum and nudged the 222 Remington into a slow death spiral. The 222 is still hanging on, but it’s a mere shadow of its former glory, even though the 223 Rem. beats its top end velocities by only 100 to at most 250 fps. Just as you can’t fight City Hall, you can’t overcome a ubiquitous military cartridge that spits free brass thither and yon. Fewer and fewer gun makers still chamber the 222 Remington.

Most 223 Remington ammo might be shot through AR-15 rifles, but bolt-actions like these from H-S Precision are oustanding platforms for accuracy and reach.

Something worth noting is that the 223 Remington usually leads in ammunition sales each year. This doesn’t mean it leads in rifle sales. Many other cartridges may be and probably are much more popular for hunting elk, deer, perhaps even coyotes. But because so many varmints, targets, cans, and dirt clods are addressed by 223 shooters each year — many of them rapid fire with autoloaders — ammo sales remain high. Not many of us go to the range and burn through 100 to 200 28 Noslers in a session.

The 223 Remington might not be the best small caliber centerfire, but until something better comes along, it’s likely to remain the most popular for decades to come.