Eye of The Buffalo

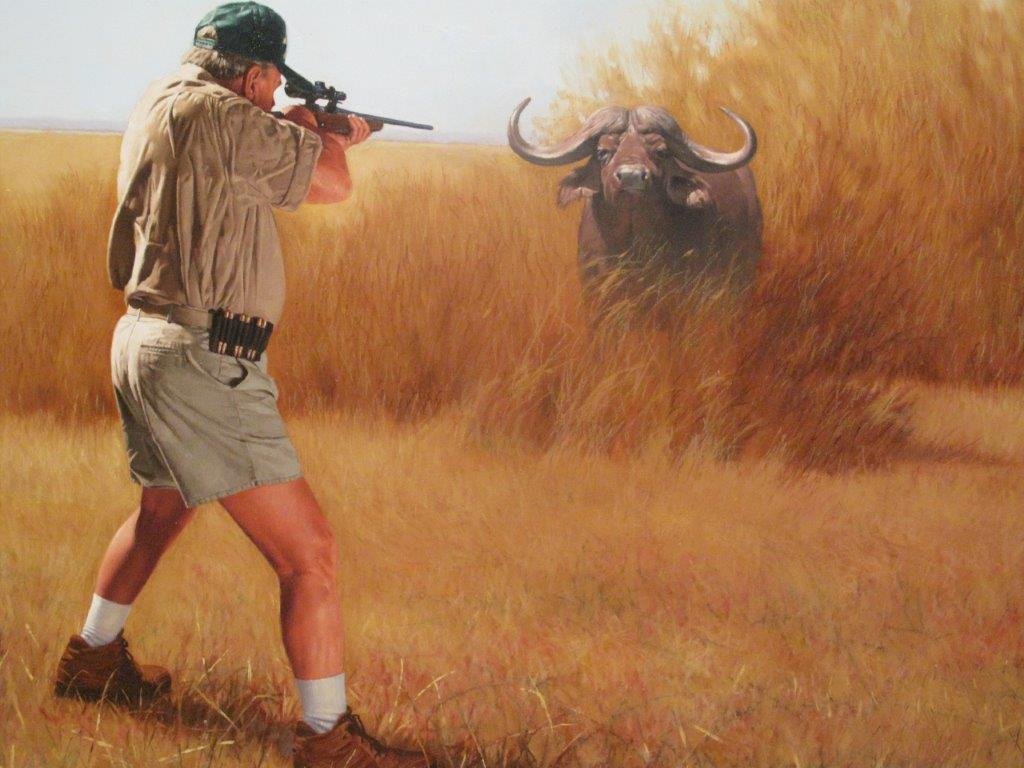

“This was not the way it was supposed to happen. I hit the Cape buffalo squarely in the chest with a .375 Holland & Holland, a cartridge the size of a banana. Nyati was supposed to go down. He didn’t even flinch! In fact, the bull trotted off with his buddies.

We had located the herd of Cape buffalo on an African plain bordering the Zambezi River, where it bulges and becomes Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe. Rob Martin, a Professional Hunter, and I set out across the plain to get a closer look. We took two trackers, December and Million, and left a third tracker, James, back in the hunting car with my wife, Betty.

I was on a 14-day hunt with Russ Broom Safaris Limited, an outfitter in Zimbabwe. However, most of the details for my hunt were handled by Jack Atcheson & Sons, a booking agent in Butte, Montana. Betty and I made the 18-hour flight on South African Airways from New York to Johannesburg and Harare, where we picked up a bush plane flight to a dirt strip near our tent camp on the Zambezi.

The African plain we were crossing was a bug-infested marsh of golden grass. Insects I’d never seen before swarmed and buzzed around my bare legs and head. Every step squished water up around my ankles. It was a hot October day, well into the 90s, and the Zimbabwe spring was just beginning. There was no escape or cover from the searing sun.

We got within 200 yards of the herd when we discovered that a small body of water separated us from the buffalo. Rob solved the problem by borrowing a small dugout canoe from two nearby fishermen in trade for buffalo meat. The fishermen even agreed to paddle us across the hundred yards or so of open water to a small mound about 75 yards from the herd, where we could get a closer look, and I could get off a good shot.

Rob waited until we got halfway across the open water to warn me about the crocodiles in these marshy waters. It was not until then that I noticed the one inch of freeboard in the small, overloaded dugout. Any more reminders like that, and I’d wish I was back in my treestand hunting whitetails.

When we reached the mound, I slopped down in a prone position. Rob and I picked out the biggest bull, which was easy because he stood a full foot taller at the shoulder than the rest of the herd. I hit him squarely in the chest with my .375. That’s when he didn’t even flinch. Almost defiantly, the bull just trotted off.

The Cape buffalo, if you keep your distance, is comparatively docile. Surprise him in close quarters, however, and he is a dangerous animal. Put a bullet in him, and he becomes extremely dangerous, frequently lying in wait to kill whoever ruined his day or any unsuspecting villager who happens to be passing by.

The Cape buffalo was the only African game that terrified Robert Ruark, a writer who literally made a career of hunting in Africa. Ruark wrote, “His horns are ideally adapted for hooking, and one hook can unzip a man from crotch to throat. He delights in dancing on the prone carcass of a victim, and the man who provides the platform is generally collected with a trowel.”

I remembered Ruark’s words when Rob and I started to follow the wounded buffalo. The dugout canoe went back for Million and December, who quickly joined us. We lost track of the big bull in the herd, and this made matters worse because we had to get even closer than killing range to locate the right bull without spooking the entire herd. It became a stop-and-go hunt. We also discovered that we were blocking the herd’s path out of that marsh.

“If the herd decides to leave the marsh,” said Rob, “run like hell for the boat.”

“Buffalo won’t go into the water?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” Rob replied, “but if they run over you in the water, you won’t get hurt bad in the soft mud.”

I thought Rob was kidding until he told me about Alstair Hull, a Professional Hunter. Hull was making a video of a buffalo herd on a small island on the Zambezi River. The herd apparently felt threatened by Hull, who was between the island and the mainland, and the buffalo stampeded. Knowing he couldn’t get out of the way fast enough, Hull laid down in the soft mud, and the herd ran over him.

“Alstair got banged up badly,” said Rob, “but at least he’s still alive.”

Following the herd was more difficult than it sounds. The grass was only knee-high marsh, and the herd could see us plainly. Whenever we got within range, the buffalo would trot off in their peculiar rocking-horse gait. After an hour of stop and go stalking, we got close enough to locate the wounded bull with his huge black hump.

Using a shooting stick, I hit him again with the .375 in the chest, and again he didn’t flinch. The bull just pointed his nose at me and gave me a death stare that twisted my stomach. His horns swept down, pushing down his ears, then hooked up in a grotesque-looking bonnet. The bull then sauntered off with the second 300-grain bullet in his breadbasket.

“What does it take to knock him down?” I asked.

“That bull weighs more than 2,000 pounds, and he’s all muscle,” said Rob. “You can’t kill an animal like that with one shot. Even when you do kill him, the bull’s brain never tells the body that it’s dead.”

We knew we would have to get closer to the herd. Nearly two hours had passed. When we moved, the herd moved. Finally, we spotted a patch of high marsh reeds at least 10 feet high. With some luck, we could use the reeds to cover our movement and get closer to the herd and the wounded bull.

December and Million again took the lead as we approached the high grass. As we moved closer to the high grass, I could see the herd about 200 yards away. The buffalo were nervous, but they were not moving off. Our plan was working. I started to glass the herd, looking for the high telltale hump of the bull.

I started to slip around the high grass, no more than 15 yards or so from the edge, when December suddenly stopped and started to shout and point at the tall grass. There was my bull, glaring at me about 15 yards away! Had the bull dropped back because he was hurt bad… or did he drop back to wait for us to get within range of his horns and his hubcap-size hoofs? I’ll never know for sure.

“Shoot!” Rob shouted. “Quick! Now!” I put the crosshairs on the bull’s chest and fired. This time the .375 knocked the buffalo off his feet, and the bull went down. I could see the black mass, but he was now partially covered by the grass.

Our trackers, December and Million, dropped to the rear for the first time since I took my first shot. I put another cartridge in the magazine, and Rob and I closed in on the bull to make sure he was down for keeps. He wasn’t!

If the bull had charged, Rob, who was carrying a .458 Winchester Model 70, still wanted me to aim for the chest, where I would hit the heart and lung area. When a Cape buffalo charges, he doesn’t lower his head. He lifts his nose, and his head is nearly horizontal. You can’t get a bullet through the massive boss that covers the top of his head. Hit the boss, and you may knock out the bull, but you won’t kill him. Even a bullet between the eyes might not reach the brain.

When Rob and I got within a few feet of the bull, he reared up his head and tried to get up. I put a final shot into his neck. We heard the death rattle and the bull finally died… but, like many animals in Africa, he did not give up easily.

Also, immediately, Million religiously held the bull’s tail in his hands and tied the hair into a knot. “Million is sending your bull on his way,” explained Rob.

The bull was the toughest animal I had ever encountered in more than 40 years of hunting big game. But Africa breeds a different kind of animal. Most big-game animals in Africa learn quickly how to run for their lives and almost always die hard. Africa is a country of predators. Everything chases and eats everything else.

My Cape buffalo hunt was over, but it did not happen quickly. We followed that wounded bull for three and a half hours while Betty waited in the hunting car. Rob would not leave her alone, though my wife thought she was alone for a couple of hours until she discovered that James had quietly and undetected found refuge from the sun by crawling underneath the hunting car.

My buffalo was not wasted. Million and December used skinning knives and homemade Batonka axes, the basic bush tool of the Batonka Tribe with an indestructible ax handle made from the crotch of the Mopane tree. My bull was quickly skinned and quartered. We gave some meat to the fishermen who loaned us their boat, and the rest was distributed to a nearby village on the banks of the Kariba. We also traded meat for fish, which we steamed that night over an open fire in our tent camp.

December carried the cape and horns back to the hunting car. When I got there, I took a close look at the massive boss. There was no gap between the horns, a sign that this bull had been around a couple of decades.

“An old bull,” I said to December.

“Yes, Sir,” said December, nearly laughing, “the old man shoots the old man!” It was a fine compliment.

I felt good about the hunt. It was a great day with exciting and scary moments. I hunted leopard, kudu, eland, impala, warthog, and zebra during the remainder of my safari, but it will be the buffalo hunt I will remember.

It’s difficult not to suddenly fall in love with Africa… with all her sights, sounds, and smells… and to respect the people. Rob Martin, a professional hunter, became a security blanket. When a herd of elephants surrounded Rob, Betty, and me, he told us to stand perfectly still while he tapped his gun barrel with a cartridge. The elephants, unfamiliar with the strange metallic sound, quietly moved off like giant gray boulders with legs.

I also watched Rob use his hands to cover the open eyes of a kudu I shot. “It will die more quickly,” he explained, “if it sees only darkness.”

Our trackers carried no rifles and put their lives on the line every day while searching the ground for tracks. December and Million, an ageless tracker with several wives and nearly two dozen children, had an almost childlike dependency and faith that Rob would be able to stop any animal that tried to hurt them.

However, there are times when even the most experienced professional hunter finds himself in a tight spot where everything seems to go wrong. On one of his hunts in Zambia, Rob was waiting for a leopard to show on one of his baits. When his hunter finally got a shot, he hit the spotted cat in the foot, and it ran off into heavy cover along a riverbank.

Rob’s client was blind in one eye and would likely not be able to see or stop a wounded leopard if it came at him from his blindside. Rob decided to follow the cat alone with one tracker and a 12-gauge shotgun loaded with OO Buckshot. When Rob approached the riverbank, the leopard immediately charged. He got off one shot, but it didn’t stop the leopard. Rob grabbed the cat’s head, but it still bit him several times in the shoulder and clawed his arms and neck. In a desperate move, Rob succeeded in shoving the cat away from his body, and it ran off.

Rob returned to camp, cleaned his wounds, and went back again to find the wounded leopard. This time he carried a .375 Holland & Holland. The leopard did not leave the riverbank, and when Rob showed up again, the cat immediately charged a second time. Rob shot, and the leopard dropped at his feet.

These are the tales of hunting in Africa. For the hunter, it is still a place to experience a challenge that would be hard to comprehend by anyone except a hunter who understands the seriousness of taking an animal’s life. I will return to Africa, and I hope to experience the excitement and fear of facing such majestic animals once again.

Obituary

Danie Viljoen, a gallant hunter with a prolific kill record, passed away doing what he loved most. A wounded Cape buffalo, the victim of an errant shot from Viljoen’s Martini-Henry rifle, stalked the young man before goring him to death. His next of kin have requested he be buried on the southern bank of the Zambezi River, Viljoen’s hunting ground. —The Victoria Falls Advertiser, Monday, October 3, 1910.

If You Go

Hunting in Africa is not inexpensive, but it is within reach of any hunter who regularly books outfitters to hunt elk, bear, sheep, or any other big game in North America. Here, for example, are some packages prices from Russ Broom Safaris for hunts in Zimbabwe:

7-Day Buffalo Safari…………………………………………. $6,500

10-Day Buffalo/Plains Game Safari…………………………... $7,000

14-Day Leopard/Two Buffalo Bulls/Plains Game Safari……. $9,800

These prices are for 1 PH (Professional Hunter) with one client. The prices are lower for 1 PH with two clients. The package rate includes everything except airfare and license or trophy fees.

Here’s a sample of the current trophy fees in Zimbabwe:

Buffalo……………….$2,000

Kudu………………….$ 850

Impala………………. $ 200

Eland…………………$ 1,100

Leopard………………$3,000

Warthog………………$ 250

Lion…………………...$4,500

Sable………………….$2,250

Crocodile……………..$1,850

Bushbuck……………$ 600

According to Rob Martin, the most popular safaris are the Buffalo/Plains Game Hunts with Cape Buffalo and Kudu, the most sought-after game animals. You can get complete information on how to plan a safari by contacting:

Jack Atcheson & Sons, Inc.

3210 Ottawa Street

Butte, Montana 59701

406-782-2382

Email: office@atcheson.com

Russ Broom Safaris Ltd.

P/Bag BW 6236

Borrowdale

Harare

Zimbabwe

TEL/FAX 263-4-860290

For travel information contact:

South African Airways

9841 Airport Boulevard, Suite 1530

Los Angeles, California 90045